Much of the focus during a 2018 research day for pistachio growers was related to aflatoxin and a related mycotoxin, which contaminate pistachios and other nut crops after they are produced by molds in orchards.

Bob Klein, manager of the Pistachio Research Board, told growers that for California pistachios to stay successful in European markets, reject percentages can’t rise too high.

The picture he painted was somewhat scary:

“About 25-30 percent of our crop goes to the EU, and the EU is one of the markets that regularly tests (for aflatoxin),” Klein said. “They regulate, and they regulate stringently.”

There’s a new mycotoxin that’s causing as many rejected shipments as aflatoxin, Klein said, and its name is Ochratoxin A, or OTA for short.

So what are growers to do? Much of Klein’s advice boiled down to integrated pest management techniques for navel orangeworm, which often coincides with mycotoxin damage.

AF36, a possible new tool for aflatoxin

But later in the day, UC Davis professor Themis Michailidies shared even more specific tips, seen above. That included another potential new avenue for growers to protect their crop from toxins. For a webcast of his full presentation, click here.

Aflatoxin is produced by Aspergillus, a mold, Michailidies said, and it can be fought with biocontrols.

He said a colleague has used that method for years to fight aflatoxin in cotton and corn, so he investigated whether it would work in orchards.

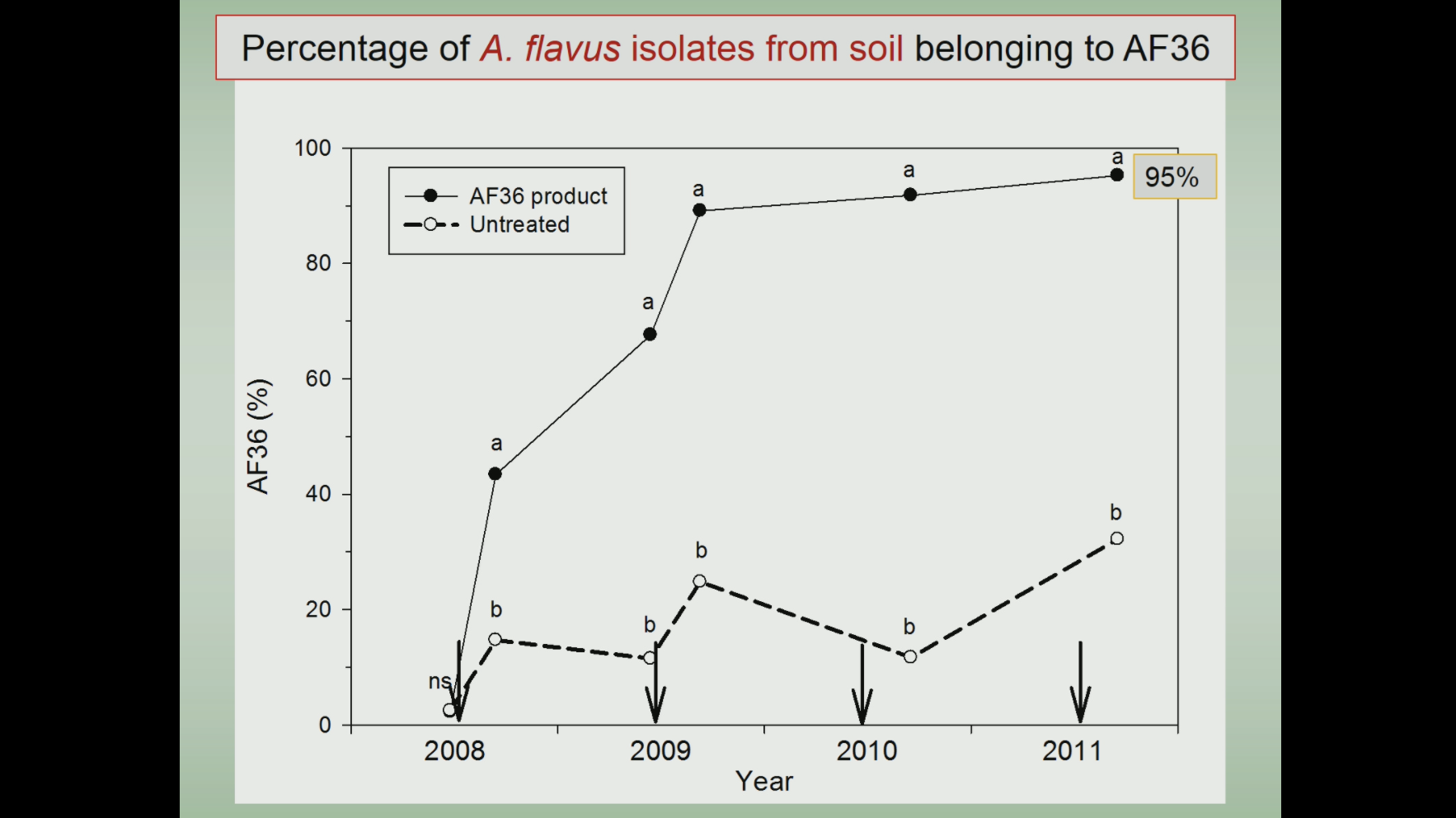

What did he find? He spread innoculum for AF36, the less toxic mold, in fields, and within a few seasons, it grew to become 95% of the population, occupying sites that otherwise would be hosts for toxin-producing molds.

Most of the AF36 seed should be spread where water will touch it, so innoculum will spread.

He told the growers that in those orchards, his team found an average of 40% less aflatoxin damage, and 55% less in reshakes, when damage is often worse.

The displacement reached 95% in the study, which ran from 2008 to 2011.

The product, AF36 Prevail, was approved for pistachios in 2016, and for almonds and figs and other crops in 2017.

In 2012 to 2014, there was a twist: the product didn’t cause drops in damage for aflatoxin.

Michailidies said it could be due to different irrigation practices between Arizona cotton and California almonds. Water is necessary to get the replacement mold to sporulate.

Another factor?

“We know now with research that navel orangeworm is a carrier of Aspergillus,” he said, adding that can affect the efficacy of the AF36 treatment as well.

So what does it all mean for growers?

Integrated pest management is still necessary for prevention of navel orangeworm. For more tips on handling navel orangeworm, see our previous blog.

Challenges facing growers who spread AF36, Michailidies said, include:

- roly polies and birds eat the treated sorghum that contains AF36

- growers may need to increase the rate of application from 10 pounds / acre

- avoid covering innoculum by plowing or with too much water

- do not apply herbicides within 1-2 weeks

Michailidies said his team is still working to figure out how to increase the effectiveness of AF36, including wetting the seed, and other tweaks to the application equation.

Ceres Imaging, which helps growers solve irrigation problems, nitrogen and soil issues, and pest and disease problems, will continue to cover the issue.